by MELVIN J. MAAS

as told to Paul F. Healy

The Saturday Evening POST

September 5, 1959

$.15

Page 30

Don’t Pity

A retired and blinded marine general offers his personal case as evidence that the disabled are people like everyone else.

The telephone rang in my room at the Bethesda Naval Hospital and when I answered I heard an old friend, Robert Copsey, a brigadier general in the Air Force Reserve, asking what I was doing there.

“Bob,”

I told him, “you remember how I always admired beautiful women. Well, now all women

are beautiful.”

Copsey got

the point that I had gone blind, and that I was adjusting to my condition and no longer

felt sorry for myself. Since that day in

September 1951, quite a number of people have seemed startled by my ability to take my

blindness lightly. They express astonishment, too, that I continue to travel alone all

over the world in the last seven years I have covered 600,000 miles, to Europe, Central

America, all United States territories and every one of the states. This travel without

any escort, human or canine, has been part of my job as chairman of the President’s

Committee on the Employment of the Physically Handicapped.

What the

public doesn’t seem to realize, I find, is how millions of severely handicapped

persons have readjusted their lives and have the ability of playing a positive, productive

part in society. In my own case, the fact that I could joke about my trouble was the first

sign that my rehabilitation was getting under way. It was a most welcome sign, too,

because when I first learned that I was doomed to darkness, I was terrified and afraid

that I would never be able to make the transition to a strange new life.

My blindness

occurred with little warning in the middle of a busy career. For sixteen years I had been

a congressman from Minnesota, and for ten of those years had served on the House Naval

Affairs Committee. I had been a flier in both world wars, and after the end of World War

II had been active as a brigadier general in the Marine Corps Reserve. Then, in July of

1950, just after the Korean War broke out, I was recalled to active duty in the Pentagon

as chairman of a Defense Department committee assigned to draft an armed-forces-reserve

reorganization bill.

While

testifying for this bill during the summer of 1951 I developed a severe case of ulcers and

on August twenty-eighth was admitted to the Bethesda Naval Hospital. That very day my eyes began to hemorrhage, and the

sight of my right eye began to fail.

Two weeks

later a Navy doctor sat down by my bed and said bluntly, “You*re a marine and

supposed to be able to take it, so we*re laying it on the line—you*re going to be

completely blind, and in all probability it will be permanent.” I was stunned

speechless. The doctor went on to explain

that the blindness apparently had no connection with the ulcers and might have been

caused by anyone of a hundred things, including bombing injuries I had suffered on Okinawa

in World War II. When the doctor left, my

first feeling was one of desperation. I had

terrible visions of sitting on a street corner~ selling pencils or shoelaces. For two nights I lay in a cold sweat. I never actually contemplated suicide, but I was

all too aware that I was in a room next to the one from which a depressed James V.

Forrestal, former Secretary of Defense, had gone to his death through a window in 1949.

My two

immediate worries were that my income would be cut off and that I would be rejected

socially. For the first time in my life, at

fifty-three years of age, I faced the prospect of being utterly useless. I was afraid that I would be unable to support my

family and would be a burden to them as well. I

wondered if my family might not be better off if I were dead and they had my life

insurance.

This period

of black depression might have clamped down on me for weeks or even months—but I was

too busy. I was still working on that

reorganization bill. I was on the telephone

all day every weekday, discussing its progress with the congressmen who were guiding it

through the House.

On the third

night my panic ended. I was able to summon up

a philosophy that had helped me before. It

is: If you are faced with a problem and can do anything about it, get busy and do it. If your problem is something you can*t do anything

about, then it is senseless to worry about it.

I began to

wonder what I could do about my problem, and I began to experiment. I still had some sight in my left eye, but I

wondered what life would be like when that was gone.

One morning I kept my eyes tightly shut as I got out of bed; I went to the bathroom

and showered, shaved and brushed my teeth without peeking once. This test brought me profound relief. If I could do that much without any trouble, life

couldn’t be so bad.

My

re-evaluation of myself started. First I

realized that I wouldn’t be penniless, as I had imagined during the period of

initial shock. Any officer in the armed

forces who is retired for total disability nets 75 percent of the base pay of his

retirement grade, and this is exempt from income tax.

As it turned Out, I had reached the rank of major general by the time I retired,

and thus began drawing approximately $900 a month, tax-free. Also, some years before I had bought an

accident-insurance policy that brings me a substantial monthly income.

Meanwhile,

the psychological readjustment with my wife, Kathy, and my four children was starting

out well. Kathy set an example by treating me

just right— with encouragement and adequate sympathy but without coddling or

maudlin sentiment. One day she brought me a

brochure, which described the rehabilitation course at the Veterans Administration

Hospital at Hines, Illinois. My

religion—I am a Catholic—has taught me that if I had the will to take

advantage of the compensations, God would give me the strength and confidence. The brochure said that upon completion of the

Hines course a person should be able to do everything he could before he went blind except

drive a car. The course lived up to its

promise.

My training

at Hines started in November 1951, as soon as I was able to leave the Naval Hospital. And at Hines I found myself-witlf2T500

others—mostly Korean War veterans—in the same predicament as myself, but

learning things, which make it possible for them to lead an almost normal life. Their constant self-kidding was wonderful for the

morale of all of us. The whole course was

designed to give us confidence—to rid us of the fear that we might become social

pariahs. Even the compulsory dancing class

with the Red Cross girls had this aim, though it took me a while to appreciate it.

The first of

these dances, when a Red Cross girl asked me to dance, I tried to beg off with the old

chestnut, “I broke my leg in China.” She didn’t back down but pulled me to

my feet with the remark, “Oh, come on, general.

If you enjoy dancing, you close your eyes anyway.” After we had danced awhile,

my partner asked me how I was getting along at Hines, and I admitted that I was having

some trouble learning Braille. “Just

remember one thing,” she quipped. “Confine

your practicing to paper.” At Hines I soon acquired a state of mind, which, I am

convinced, is one of the most important mental aids to the handicapped. I learned to regard my existence as a continual

challenge, full of the excitement of discovery. When

I woke up in the morning, I asked myself, “What new things can I learn

today—things that I once thought could be done only with sight?”

In fact, I

sometimes tried to do more than the course permitted.

That’s how I came to drive a car. One

January day my instructor took me on an assignment in an outlying neighborhood. He parked his car at an angle. When we returned, a heavy snow was falling. The car*s wheels spun when we tried to back out,

so I persuaded the instructor to get out and push while I took the wheel. I was able to back the car into the middle of the

street. Then I couldn’t resist shifting

gears and driving forward a short distance. The

instructor got back behind the steering wheel with a memorable sigh of relief.

The Hines

brochure had not bothered to rule out flying an airplane, and I had never heard of anyone

literally flying blind. Yet, one time when I

was returning from Hines to Washington, D.C., in a Marine Corps transport plane, I

suddenly got the urge to take the controls again. After

all, I had logged between 8000 and 9000 hours as a marine pilot, and some of those hours

had been fairly exciting. In fact, one of

them had been downright stupid. That was back

in 1931 when some of my colleagues in the House of Representatives scoffed at my notion

that an enemy plane could get close enough to bomb the Capitol. To show them, I borrowed an old pursuit plane

from nearby Bolling Field and made three screaming runs on the skylight of the Rouse while

it was in session. Members told me later the

vibrations shook some plaster from the ceiling—and emptied the House in record time. Foolish though this stunt was, it proved my point.

Well, on

this trip back to Washington in 1952 I asked the pilot, whom I knew well, to let me take

his seat. He yielded, and I enjoyed myself

thoroughly. After about ten minutes the

copilot leaned over and said respectfully, “General, you’ve made a ninety-degree

turn to the right.” Following the usual procedure, I twisted the controls over to the

left and held them there for fifteen seconds to compensate.

I said, “Well, son, how’s that?” He replied, “Fine, general,

except that you’ve made a 150-degree correction.” When I returned to the cabin,

I sat with a group of young marines hitchhiking a ride back to the capital. I said, “Boys, you don’t know it, but

you’ve just been piloted by the blindest blind pilot in the business.” They

laughed and one of them spoke up.

“But,

general,” he said, “you were doing swell—especially on that 360-degree

turn.” This was interesting news. The

copilot, a first lieutenant, apparently had been too shy to tell a blind general that he

was flying in circles.

So I gave up

flying. But I have never given up reviewing

parades. At first it seemed silly, but now it

seems perfectly natural. I can enjoy the

music, and my memory of thousands of other parades helps me to visualize the scene. In fact, with someone giving me a description of

what’s passing—and nudging me when to salute the flag—I can practically see

the whole thing.

Despite my

blindness, I was kept on active duty at the Pentagon until August 1, 1952, because my

advice was needed on technical amendments to the Reserve bill before it finally passed the

Senate. During the next three years I was

recalled to active duty to serve in full uniform at meetings of the Reserve Forces Policy

Board, of which I was a member. Also, I

served intermittently on active duty as a member of promotion boards in the Marine Corps.

One day an

Army general remarked that I was probably the only general in history to remain on active

duty while blind. “Oh, no,

general,” I said, “only the first to admit it.” When the President’s

Committee on the Employment of the Physically Handicapped was created in 1947, President

Truman had appointed me as a member, presumably to represent the military reserves. In April 1954, President Eisenhower asked me to

step up to the job of chairman. I tried to

convince the President that a sighted person could do a better job than I could. But I lost this argument with Ike, who had been a

friend of mine since he was an Army major assigned to the War Department.

Our

committee does not find specific jobs for the disabled.

Its purpose is to educate employers in the practical advantages of hiring the

handicapped. Our program is carried on

through radio and television programs donated by industry, free advertising and newspaper

space job opportunity tips handled through the AFL-CIO, consultation with state and lo cal

governments and many other ways.

The

committee has fifteen salaried workers plus its non-compensated chairman and 300 committee

members representing civic, fraternal, labor, veterans and other national groups. Mine is primarily a public-relations job. I give three or four speeches a week before all

types of luncheon and dinner meetings. Almost

all my trips are by air, and I am usually met at the airport by members of the group I am

scheduled to address. My first European

trip after becoming blind was in 1953. After

attending an international veterans’ rehabilitation conference at The Hague, I went

on to Paris to take up a military matter with my boyhood friend, Gen. Alfred Gruenther,

then supreme commander of NATO and now president of the American Red Cross. After chatting with me for a while, Gruenther

asked, “Who’s with you, Mel?” “No one,” I said. “No one?” he echoed. From the tone of his voice I could tell that he

didn’t believe me. So I explained that

on my first trip as a blind man an escort had come along, but had become so airsick that I

had to take care of the escort. After that I

had decided to go it alone.

Only once

has there been a serious mix-up in my solo travel arrangements.

In December

1957, I flew to Guatemala City to address an Inter-American conference. I had been told the reception committee would

include quite a number of lovely young ladies. But

no one at all was there to greet me at the bottom of the ramp. I followed the other passengers into the terminal

by the sound of their heels—but still no one welcomed me. For the first and only time in my foreign travels,

I felt keenly my total ignorance of foreign languages.

After

standing around helplessly, I recalled the name of the hotel I was booked into, and

desperately began calling out, “San Carlos Hotel!

San Carlos Hotel!” Nothing happened. People

must have thought I was a barker for the hotel.

After a half

hour, however, a perceptive taxi driver took pity on me and delivered me to the San

Carlos. There my hosts explained the

mix-up—I had not been expected until the next day.

In the

United States if no one meets me at the airport, I ask a skycap to get me a taxi. The taxi driver, the hotel doorman and the

bellhops take over from there.

When the

bellhop shows me to my room I ask him to take me completely around it, identifying each

piece of furniture.

When he

leaves the room, I feel my way around the walls again.

After that it’s just as if I could see the room.

When I

travel, my schedule usually puts me in a different city every day.

Early one

morning I woke up and couldn’t remember where the bathroom was in the room I was

occupying. Then I realized I didn’t even

know what city I was in. Having no

alternative, I called the switchboard operator and timidly asked her where I was. Before she told me I was in Cleveland, Ohio, I

could overhear her turn to another operator and say, “Boy, has this guy been on a

bender!” One of the first problems I faced in traveling was that the hotel maid

invariably put my bedroom slippers some place where it was almost impossible for me to

find them. Now, before I leave my room I

make a point of hiding my slippers from the maid—usually in a dresser

drawer—before she can hide them from me.

Like other

physically handicapped persons who get around, I find that the biggest hazard is the

well-meaning but thoughtless person who is determined to help me. It seems to be a natural inclination to grab a

blind person by the arm and shove him along. But

if I’m shoved out in front of a sighted person, it means I come to the curb first, or

I am pushed, into revolving doors ahead-of him. However,

if he lets me take his arm, then I’m a half step behind him and can tell by the feel

of his arm anything he’s about to do, such as turning or going downstairs.

For some

reason it’s very hard to• get people to do that.

I finally -got to the point where I just let them shove me.

I’ve

come home from trips with my eyes black and blue or my-flesh bruised. Once I suffered a broken rib. A fellow judged to be about six feet, six inches

tall—nearly a foot taller than I am—held me in a vise-like grip and propelled me

toward a door.

He went

through the center of the door, but I slammed against the doorjamb.

Many people

tell me I do not look blind at first glance, and nothing tickles me more than to be

mistaken for a sighted person. When I go to

the hotel dining room, for example, I ask a waiter to read me the menu. One waiter misunderstood and said apologetically,

“Mister, I’m just as ignorant as you are,”

I don’t

wear dark glasses or carry a white cane. A

long cane gets in my way in airplanes, in restaurants, and so forth, so I use the

collapsible leg of a camera tripod. It can

be folded and put into my pocket when I don’t need it to warn me of steps and to

measure the height of curbstones.

From the

beginning I was determined to avoid the telltale characteristics of

the blind. At Hines, my instructor drilled me in turning my

head toward the person I was addressing, “watching” the smoke curling up from my

cigar and in other habits of the normal person.

To avoid

using Braille notes on the dais, - I memorize the substance of my speeches. As soon as I have been introduced, I usually say,

“I know what I’m talking about because I’m handicapped too.” Then as a

sympathetic hush settles over the audience, I add, “I’ve got false teeth!”

I can hear the tension snap. A burst of

laughter follows, and from then on I’ve got my listeners where I want them.

Some of my

more amusing experiences are woven into my message. Once,

for example, when my wife drove me to the Washington airport for a trip to Miami, Florida,

she discovered before I boarded the plane that I was wearing a brown checked sport jacket

with gray trousers, gray vest and gray accessories. Although

I use Braille labels on my coat hangers to prevent exactly this sort of confusion, I had

made a mistake that morning. So I had to go

on to Miami in my scrambled ensemble. When I

rose to speak on the program I explained what had happened.

“And

you know what my wife said to me?” I told the audience. “She said,

"Now

you’re not only blind but color blind!" Humor is a wonderful safety valve for a

handicapped person. At a West Coast factory I

was with a blind youth who was pushing a paraplegic to the cafeteria in a wheel chair, the

paraplegic giving the directions. When the

wheel chair bumped the wall slightly, the paraplegic wisecracked, “Hey, look where

you’re going!” “If you don’t like my driving,” the blind youth

shot back, “get out and walk.”

It would

seem obvious that sighted people should immediately identify themselves when addressing a

blind person, but they often forget this amenity.. Sometimes

the results are funny. Not long ago a blind

former Army pilot gleefully told me about going to a cocktail party where a woman greeted

him by throwing her arms around his neck and kissing him.

He-

reciprocated. But when the woman broke from

the affectionate clinch, he amused onlookers by inquiring, “Say, just who are

you?’

She was, of

course, an old friend, but not until she spoke could he be sure which old friend. I told him I could appreciate his problem because

I’ve had the same pleasant experience several times.

Learning to

compensate for lack of sight has been a constant challenge.

Formerly when traveling -I would read or look at the landscape. Now I have trained myself to use this time to

concentrate on the tasks at hand or to meditate. I

believe I have learned to think more clearly than I could before I became blind.

A by-product

of this concentration has been a tremendous development of my memory—it has become

far more retentive than I ever imagined it could be.

For example,

while I was on the Reserve Forces Policy Board, several members once challenged my

-detailed recollection of the testimony a general had given-the day before. They got out their copies of the general’s

statement and discovered that I was right. Dr.

Arthur Adams, then chairman of the board, was deeply impressed and asked me how I

remembered the involved testimony so clearly.

“Well,

Mr. Chairman,” I said. “I have an

advantage—I’m not handicapped by sight.”

Since I

can’t use a telephone directory, I have trained myself to remember some 200 telephone

numbers and as many extension numbers. Also,

I have developed my own system for dialing, which is faster than that used by the normal

sighted person. If you doubt this claim, let

me explain that I don’t have to lose any time looking for the next number, and

instead of waiting for the dial to spring back by itself after each movement, I move it

back with my finger to give me the reference point for the next digit.

Thanks to

modern science, my life at home is anything but that “separate dark world” which

traditionally was thought to be the lot of the blind.

I am virtually self-sufficient in my soundproofed “office” in the

basement of my Washington suburban house, where I live with Kathy and my eighteen-year old

son, Melvin, Jr. My three daughters are now

on their own—two are married and one is a captain in the Marine Corps.

Surrounding

my chair are a Braille writing machine, a dictating machine, a pocket-size tape recorder,

an “intercom” connecting me with the upstairs, a radio and the audio part of a

television set.

There are

many TV discussion programs and detective plays which, with a little imagination, I can

enjoy probably as much as people who watch them. And

I take in—effortlessly—more good literature than ever before by listening for

hours on end to my “talking book” records which, incidentally, are provided free

by the Library of Congress to all blind citizens of this country. On the whole, I am busier perhaps than I ever have

been. I belong to seventy-two

organizations—local, national and international —and am quite active in twenty

of them.

The degree

to which a handicapped person can become usefully busy obviously is the most important key

to his readjustment. On the President’s

committee, we define a physically handicapped person as “one who has a condition

which makes normal employment difficult.” We believe the committee deserves some

credit for the fact that, since its start in 1947, employers in the United States have

been hiring the handicapped at a rate which now runs close to 300,000 a year. Approximately 7,500,000 handicapped persons are

now employed in this country, and we know of another 2,000,000 who are employable if the

right jobs are found.

The appalling additional fact is that on the basis of door-to-door surveys we estimate there are another 2,000,000 “hidden handicapped” who are unreached by doctors and government agencies. These are unfortunates, suffering blindness, epilepsy, palsy, and the like, who have been hidden away in back rooms or attics because their relatives imagine that some social stigma is attached to such conditions. So we apparently have a long way yet to go in convincing all Americans that the handicapped are human beings like everyone else and have the same hopes, dreams and need for dignity, asking only a positive role to play in society.

When a

person objects to working alongside a handicapped worker, he usually explains that he is

afraid an accident will happen. But this is

only an excuse and has no foundation in fact. After

searching workmen’s- compensation-law statistics all over the United States, we have

yet to find a case where a handicapped worker caused an accident to a normal worker. Indeed, in the Hughes electronics plant in Los

Angeles, 27 per cent of the work force is physically handicapped in some way, yet that

plant’s insurance rates have been reduced several times because there hasn’t

been an accident among these workers in ten years.

No, I think

the reason why a normal person is uncomfortable in the presence of the disabled goes

deeper than the purported fear of accidents. There

is a feeling that these people are basically different.

It may well be a psychological factor that can be traced to an early exposure to

the grimmer kind of fairy tales, in which deformity invariably is associated with ugliness

and evil.

Despite my

concern for this humanitarian aspect, we keep our pitch for hiring the handicapped on a

purely practical basis. Not only do they have

a better accident record than their coworkers but the handicapped out-produce them, and

demonstrate more ingenuity in doing a job better or faster.

Actually, of course, every handicapped person is— of necessity—an

inventor.

My own

success in drastically rebuilding my life is by no means unusual. In fact, whenever I pride myself on doing well, I

hear about somebody who puts me to shame. Three

years after my blindness, I confessed some momentary feeling of inadequacy to a

thirty-year-old acquaintance who has been blind since he was two and could do amazing

things.

He laughed

and said, “Oh, well, you’re just a novice.

Wait until you’ve been blind for twenty-eight years.” But at least in my

worst moments of discouragement, I never said to myself, “Why did this have to happen

to me?” After all, I feel there are few people who have had a more exciting life than

I have had. Long ago I decided I had more

than my share of good fortune, and I still have. My

greatest compensation comes from people who approach me gratefully after a speech. Many a mother has said that I have given her hope

for the future of her blind child. Others

have said, “I’ll never feel sorry for myself again.” My seven-year-old

grandson, Marty Martino, summed it all up better than anyone else. When he got on my knee and I explained how I was

able to get around, he said, “I’ve got it, grandfather—you can see with

everything but your eyes!“

Despite his blindness Maas travels alone on his speaking tours in this country and abroad. He never wears dark glasses and, instead of a cane, he uses a compressed leg of a camera tripod.

(PHOTO 2)

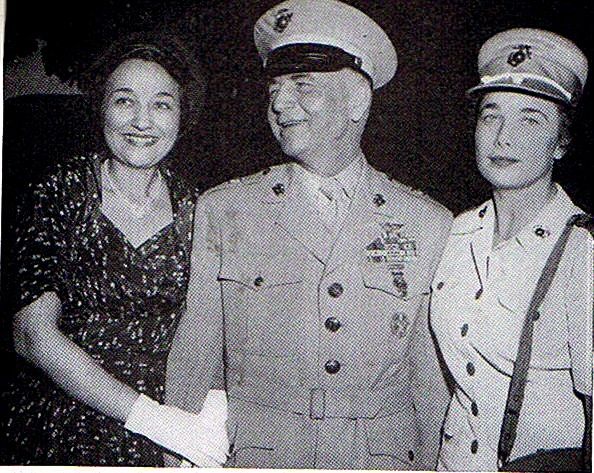

The author with his wife Katherine (left) and their daughter Patricia on the day of his retirement in 1952. He had continued at his Pentagon job one year after he lost his sight. Patricia is now a captain in the Women Marines.

Additional Information:

1898 - Born, May 14.

1919 - Graduated from St. Thomas College at St. Paul.

1927-1933 Republican to Congress; unsuccessful candidate in 1932.

1932 - Received the Carnegie Silver Medal for disarming a maniac in the

United States House of Representatives.(see note 1 below)

1935-1945 Republican to Congress; unsuccessful candidate in 1944.

1918-1919 - World War I, served in the aviation branch of the Marine

Corps.

1925 - Officer in the Marine Corps Reserve.

1942-1945 - Served in the South Pacific as a colonel in the Marine Corps.

1949 - Became a member of the President’s Committee on Employment of

the Physically Handicapped.

1951 - Stricken with total blindness in August at age 53.

1952 - Retired from military reserves, rank major general, August.

1953 - Vice President, BVA

1954-1964 - Served as Chairman of the President’s Committee on

Employment of the Physically Handicapped.

1958 - Melvin J. Maas, Chevy Chase,

Maryland; Named on BVA Congressional Charter.

1960 - President, BVA

1964 - Died April 13.

Reference Source:

Biographical directory of the United States

Congress,

and BVA Bulletin August 1995, 50th Anniversary Issue.

Major General Melvin J. Maas

Congressman from Minnesota for16 years

Lost eyesight in 1951 at age 53

Pilot in WWI and WW II

Interviewed for article: "Don’t Pity us Handicapped"

Saturday Evening Post, September 5, 1959. page 30

Paul F. Healy author.

Head of the President’s Commission on the Employment of a Physically Handicapped

(Note 1) In December 1932, a twenty-five-year-old department store clerk entered the

House gallery waving a loaded pistol. Dangling one foot over the railing, he demanded the

right to speak. A mad scramble for the cloakrooms ensued. Melvin J. Maas, a member from

Minnesota, quietly talked the man into surrendering his weapon. Asked by a reporter later

whether he had had experience handling deranged people, Maas replied, "Why not? I've

had six years in Congress." (Inside Congress, Ronald Kessler, 1997,Pg. 63)

Research by: Paul W. Kaminsky FRG